Podcast: Play in new window | Download

And why not let this be my wish for Moments under Lamplight? May this small lamp shine – thanks, of course, to this global internet – may it shine all over the place. Yes, “and this also has been one of the dark places of the world”, as Marlowe says about England in The Heart of Darkness. England, of course, has become much more a place of darkness since Conrad wrote that book a hundred years ago, and so has most of the once-“civilised” world – or maybe it’s just that we have become more aware of, and perhaps more accepting of, the darkness and confusion all around us. We all need to be irradiated – irradiated by healing light, of course, not by poisonous rays.

Where does this phrase come from? Well, “terras irradient” is the motto of Amherst College, and so it can be my tribute to my alma mater. But I have something a little embarrassing to confess here. I’ve always thought the phrase came from Virgil’s Aeneid, perhaps towards the end of Book VI, but I now discover that there’s no such literary connection. The phrase appears to have been created by the founders of Amherst College in 1821, as a missionary statement. – No, not a mission statement, they didn’t have those phoney tags in 1821, but a missionary statement. Amherst College, after all, began as a training college for clergymen, with a strong emphasis on missionary work. Let these missionaries go out there and bring the Gospel light to all nations.

My dear and honoured professor, Ted Baird, has written about this early missionary zeal at Amherst. “Amherst College,” says Baird, “founded for the express purpose of irradiating the world, did succeed in training men for the evangelical ministry. […] Of the 1,500 graduates [of Amherst from 1821 to 1863] 700 were ministers. […]

“Within its first twenty years, graduates of the college were in India, the Sandwich Islands, the Malay Archipelago, the Marquesas Islands, in Borneo and Patagonia, Singapore, among the Zulus of South Africa.” Not to mention in America too, irradiating the Seneca tribes, or, as Baird catalogues it, establishing churches “in expanding New York State, in Marcellus, in Chenango Forks, in Canandaigua and in the Burned-Over District. In the 1830s they moved to Illinois, and by the ’40s to Texas and Oregon, and a very few were to reach California.”

Who were these Amherst students turned into missionaries? Here’s Baird again: “Again and again there appears, almost as the only type, a boy or young man whose bodily strength was so feeble, whose health was so frail, that it early became apparent he could be of little use on the farm. Again and again one reads in the biographies of ministers of general debility, of loss of voice, of the finalities of consumption.”

The Amherst graduate Baird singles out is Henry Lyman, born in Northampton, Massachusetts, in 1809. Baird sums up his early years: “He grew up a troublesome child, and received much chastisement. When, with tears in his eyes, he begged his father to allow him to go to work in a store or on a farm, he was refused. He was sent to Amherst College.” At first a leader of the “wild part” of the student body, Lyman soon underwent a profound evangelical conversion at Amherst, and his path was set – for fanatical dedication to irradiating the world.

Once ordained, Lyman was sent out to a remote area of Sumatra, noted for its huge population of “benighted” natives, who were also, incidentally, notorious cannibals. With his companion, the Rev Samuel Munson, he proceeded across a mountain range and into dangerous territory that he was warned many times not to enter. He proceeded anyway. Zeal does not turn back. Whether through the treachery of their guides or through sheer ignorance, Lyman and Munson finally found themselves surrounded by two hundred armed warriors.

Baird gives us the facts: “They surrendered those arms they had so reluctantly carried with them and by sign language tried to express that they came in peace. They were both murdered. (The rest of the party made its escape.) The bodies of the two missionaries were cut up and devoured piecemeal. In the course of time two skulls, which by their configuration were identified as belonging to white men, were delivered to the [American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions]. There is in the Northampton cemetery a stone erected in memory of Henry Lyman. He died in his twenty-fifth year.” “The situation is clear,” Baird adds: “these men deliberately, confidently, in perfect faith walked to their certain death.”

Well, what do we make of this? as Baird might have asked his class. It seems to us today much more important that these early Amherst men should have brought a little more light to their own world rather than carrying their zealotry into other lands. They might have attended to the beam in their own eye before so confidently seeking to remove the mote in others’ eyes.

But these were real people, with real views of how to act in this world – even though we today find it hard to approve of them. As a graduate of Amherst College, I am, in some way, connected to them, and the more so as I am willingly flying this same banner they flew: “Terras Irradient”. We all carry inheritance in some way or other from biological or cultural ancestors we repudiate today. There’s no shame in honestly admitting this.

So there we are. I’m stuck with this as my college’s motto. (At least it’s not as blatant as the old dishes we used to have in the dining hall, celebrating Lord Jeffery Amherst, hero of the French and Indian War, who came up with the radical idea of giving the Indians blankets infected with smallpox and thus wiping out the enemy. Early germ warfare. Our college plates featured along the rim a depiction of the English general on horseback, sword raised threateningly, chasing scaredy-assed Redskins, looking back in fear as they fled. I think we were supposed to snigger at these savages as we ate our overcooked meat and potatoes. I’m proud to say that ours was the generation who insisted these dishes be done away with.)

These plates are gone for good, but the motto remains – and can be redeemed. Metaphors are resilient, “momentary stays against confusion”, as Robert Frost once wrote in the Amherst college newspaper. The missionary moment is over. Our Moment, under Lamplight, is, I hope, very much alive, and connected in its own way with light. We are all of us lost in Dante’s dark wood, and we need whatever glimmerings of light we can find, even if they are only momentary. Even quick flashes of light might be enough to make out the markings on a map.

And that’s what I dare to hope for this audio-blog. You can click onto this short talk, and maybe see a few things in a new way. I chat with you for a few moments: you, lost in a dark wood – as I too am lost – and together maybe we’ll find a bit of light. Or at least lighten the burden, okay?

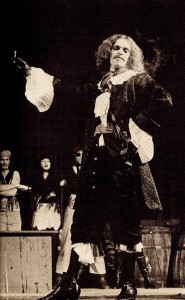

But one more thing about this phrase. I hope I am using the phrase well here, but I will never equal the time long ago when I gloriously proclaimed Terras irradient in the Kirby Theatre at Amherst College. It was my senior year, and I was on stage for the only role I have ever performed on a stage. Captain Hook, in a very unorthodox performance of the musical version of Peter Pan. With my hair down to my shoulders, a very sharp and dangerous hook custom made for me, and a wonderful, thin, crooked – but, let me tell you, absolutely vile – cigar, made in Louisville, Kentucky – I must say I made an interesting Hook.

But the problem was that we never got around to blocking the duel between Hook and Pan until about twenty minutes before the curtain went up on opening night. Artie, playing Peter Pan, wanted to use a little knife, as in the Disney cartoon, rather than a sword, as J M Barrie had written in the original script. Twenty minutes before curtain-up is not the time to calculate careful moves, and we were, frankly, pretty slap dash about this.

Came the moment for the big sword fight, and after one or two parries, me retreating before Peter’s impish boldness (no flying for this Pan since the harness had snapped at dress rehearsal), I never noticed how near to the edge of the stage I was getting, and the next moment – I had disappeared down into the lighting pit, gone from sight. I could have killed myself, or broken all the equipment. But I was only dazed. (“Yeah, come on, Robert-Louis,” said some friends afterwards, “that was a little overdone, now, wasn’t it?” Like I deliberately endangered myself like that.)

But I had one final line. In the original version, Hook jumps overboard crying out, “Floreat Etona” – May Eton flourish – showing that he was nothing more than an English gentleman, bred at the best schools, just gone a little wrong. But I wasn’t going to use that motto. No, retaining my self-possession, from the obscurity of the lighting pit, I called out for all to hear: “Terras irradient!”

Well, the last words of Captain Hook, but the opening words for us here at the start of what I hope will be many wonderful shared Moments under Lamplight. Good-bye for now.

This is a test run. The text of the blog may get a few adjustments before it’s final, but the sound recording will have to be re-recorded, in a better place than my desk.

I wondered if this episode gets too heavy, and the talk of missionaries might put some people off. But I make my position clear, and I think I lighten the tone considerably, first with the business about the plates and then with the anecdote about Captain Hook.

I’m not sure about having two pictures, especially since the Amherst picture does not make “terras irradient” very visible.

All this is up for discussion.

RLA

The thumbnail doesn’t have to be that small. It just looked funny any bigger considering how little text there is to go with it. I’m still working on a way to display the full version of a picture in the page itself, rather than opening another tab when you click on it…

Suppose there was that blurb, followed by the first paragraph of the text, with a link to an archive of texts of each episode. Does that look too complicated? Would people be interested in seeing the text as well as having the audio? I don’t know.

This is wonderful! Just as I suspected,with the ‘moment’ lasting approximately ten minutes, I’ll go away wanting more.

“Light, more light.” ; )

The Hook photo and story is classic!

I like having the text to read along.

More light indeed – so we can, like angels, fly because we take ourselves lightly.

And yes, I have also enjoyed this dual reception – eyes and ears.