Robert Louis Stevenson as a Countercultural Figure of the 1870s

Talk Presented to the Cambridge University Countercultural Studies Group

7 May 2010

RL Abrahamson

In 1882, Stevenson published a collection of his essays on a variety of writers: Villon, Victor Hugo, Walt Whitman, Henry David Thoreau, Robert Burns, John Knox, and others. He called the volume Familiar Studies of Men and Books. This talk will take on the form of a familiar study but of just one man, though many books. Like Stevenson, I will speak both about the man and his writings, and, as Stevenson carefully explained in the Preface to Familiar Studies, this will be only an impression, the development of one “point of view”. Thus the presentation will always be flawed; by its very nature it can never hope for any kind of completeness or accuracy: “the proportions of the sitter must be sacrificed to the proportions of the portrait,” as Stevenson says, “[…] and we have at best something of a caricature, at worst a calumny” (27.xiii). But then Stevenson embraced failure as an inevitable quality of human life. The fear of failure certainly was no reason to hold back. “Acts may be forgiven; not even God can forgive the hanger-back.”

So the point of view I am going to take in this discussion of Robert Louis Stevenson is his role as a countercultural figure of the 1870s, the decade of his twenties. We’ll probably need a working definition of countercultural, a term we have always kept pretty broad in this group. The countercultural figure, let’s say, is a person who disregards the conventions, and questions assumptions of the culture he or she resides in, but more than that, takes an active role in opposing these conventions and assumptions. This opposition can take many forms – individual or group action, political or literary, sustained or intermittent. Let’s see how Stevenson managed it.

I. Stevenson’s Countercultural Life up through the 70s

First, let’s look at Stevenson’s life in the 1870s. Our countercultural point of view might want to see him as in many ways analogous to the privileged, upper-middle class rebellious teenager that became one of the stereotypes of the countercultural of the 1960s. Stevenson grew up in a very respectable family in Edinburgh. His father belonged to one of the most distinguished engineering families of the time, building lighthouses around the world. Although Thomas Stevenson refused to take out patents on any of his inventions that revolutionised the effectiveness of lighthouses – his reason was that such inventions were for the public good, not for private profit – although he lost the income from these inventions, he nevertheless made enough money so that the family was spared nothing. If one of them was feeling off colour (and all three Stevensons enjoyed delicate health), they would set off on the trains to the coast, or to the south of England, or France. The family kept a carriage, and had a country cottage in Swanston, outside of Edinburgh. Thomas Stevenson proudly supported his son’s writing – as long as he approved the subject – and paid to have published the sixteen-year-old Louis’s historical account of The Pentland Rising. When Louis, aged 23, was “ordered south” for his health, his father never hesitated in supplying as much money as Louis needed for his six-month stay in Mentone, on the Riviera.

And yet, why did Louis Stevenson need to convalesce on the Riviera? When his parents heard the doctor’s instructions for a stay in a warmer climate, they immediately started planning a family holiday in Cornwall, but the doctor told the parents that on no account were they to accompany their son. The doctor knew that the parents were one of the main causes for the son’s nervous breakdown.

Again we get the 1960s picture of the upper-middle-class kid with everything, yet rebelling against his parents. In Stevenson’s case, there were two main areas of rebellion. His father planned for Stevenson to follow him into the family business. Louis signed up to study engineering at Edinburgh University, but seldom attended lectures, and when he did, it was often to ridicule the lecturer or draw in his notebook. Most of the time, however, he was roaming the streets, exploring what it was like to be an outcast in the poor neighbourhoods or mooning around in graveyards.

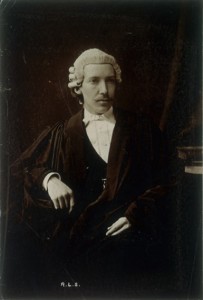

The fact was that engineering was too respectable for Stevenson, too staid. Father and son agreed on the alternative plan of studying law – equally respectable and staid, but at least with a stronger literary connection. Stevenson passed his exams (and was given a gift of £1000 by his father), but never practised law. He threw himself into a career of writing instead.

The other and more serious battle between father and son was fought over religion. Reading Darwin and Herbert Spencer confirmed his views that the Church was wrong, and Stevenson fell easily into the fashionable atheism of the 70s. He and some friends even founded a secret society: LJR (Liberty, Justice, Reverence), whose constitution began: “Disregard everything our parents have taught us.”

Louis hid this atheism as best he could from his father, a strict Presbyterian, until one day, when Louis was 22, Thomas Stevenson asked “one or two questions as to beliefs”, as Louis said in a letter later that night, “which I candidly answered. I really hate all lying so much now.” The father responded as many fathers have since, in the face of their children denying all they hold dear: with pain, puzzlement, and instilling guilt. “What did we do that was wrong?” ask the parents in the Beatles song. Here’s Thomas Stevenson’s version: “I have made my life to suit you – I have worked for you and gone out of my way for you – and the end of it is that I find you in opposition to the Lord Jesus Christ. I find everything gone.”

And yet, Thomas Stevenson was remarkably loving and never disowned his son as other parents might have done for less. Louis continued to live at home throughout his twenties, religious differences kept hidden. Most of his time in Edinburgh was spent upstairs writing, or taking part in the polite world of bourgeois Victorian Edinburgh – dinner parties with young ladies too well bred to have anything to say, and where Stevenson might show up in a formal coat, but, as in one recorded occasion, with a blue flannel shirt under the coat. And his hair, of course, was much longer than was justified even by his susceptibility to chills and draughts. And then there was the time a friend of his father’s saw him smoking on the streets of Edinburgh and gave him a lecture for such disreputable behaviour.

But increasingly he was spending less time in Edinburgh and more time in London and France, which became his primarily locations in the 70s. Let’s take London first.

Stevenson’s life in London centred around the Savile Club, where becoming a member in 1874 he was able to make contact with prominent writers and important magazine editors. My sense of the Savile Club was that most of its members stood on the side of Darwin and Spencer against formal religion. Sidney Colvin, the friend who promoted Stevenson’s writing and introduced him to the Savile Club, was recommended by Stevenson to his cousin as “one who hates God and Heaven and the soul and sich” (430) – that is, one of our sort. It was very exciting to be one of the right-thinkers who stood against religion.

When he wrote later about this time of his life, Stevenson places himself with Kingdom Clifford, a fellow member of the Savile Club and one of the loudest voices at the time against formal religious creeds that called for blind faith. “Noisy atheism,” Stevenson says

was indeed the fashion of the hour; even to the fastidious Colvin, the humblest pleasantry was welcome if it were winged against God Almighty or the Christian Church. It was my own proficiency in such remarks that gained me most credit; and my great social success of the period […] was gained by outdoing poor Clifford in a contest of schoolboy blasphemy. (29, 166-67)

The Savile member who was most helpful to Stevenson was Leslie (“father of Virginia Woolf”) Stephen, editor of the prestigious Cornhill Magazine. Stephen, one of those “noisy atheists”, had just published a collection of his own essays called Free Thinking and Plain Speaking and welcomed Stevenson as a fresh voice in the campaign against staid Victorian values. Yet at the same time, the Cornhill was pledged to contain nothing that would offend vicars or ladies. Stevenson could be counted on to promote the cause without offending those who were paying the salaries. When in 1877 Stevenson submitted his essay “Apology for Idlers” to the Cornhill, Leslie Stephen wrote back that “something more in that vein would be agreeable to his views” (Letters, II.217), and so Stevenson produced “Crabbed Age and Youth”. Both essays defy respectability by suggesting that there is more to life than just making money or condemning the younger generation for not holding the same views as the older generation holds.

Much of Stevenson’s time in London, especially in the years 77-78 was taken up with work on the weekly magazine London, co-edited and then edited by his close friend W E Henley. The magazine was not especially countercultural – though something in the second issue offended Mrs Stevenson so much that Thomas Stevenson cancelled his subscription – but what was offensive to many of Stevenson’s Edinburgh supporters was the simple fact that he was wasting his time being a journalist. Stevenson was caught up in the dashing, disreputable life of a newspaper. And they were right. Although Stevenson seems to have had a good time dashing around London, writing nonsense at the last minute to fill a column, he was wasting his abilities and his time, and the disreputable air he took on was just superficial. The newspaper did not really give him scope to address the countercultural issues on his mind. Nevertheless, even in a trivial piece such as his “Plea for Gas Lamps”, he expressed his opposition to the new electric street lights coming to London not on technical grounds, or financial grounds, or even safety – but on aesthetic grounds. The light cast is “horrible, unearthly, obnoxious to the human eye; a lamp for a nightmare! Such a light as this should shine only on murders and public crime, or along the corridors of lunatic asylums, a horror to heighten horrors” (25, 132). You see the way the journalistic demands turn his prose a little melodramatic, but you can also see the impulse to outrage standard public opinion – on legitimate grounds.

The Cornhill became Stevenson’s chief vehicle, both for his essays and fiction. In the eight years from his first essay on Victor Hugo in 1874 until 1882, when Leslie Stephen left the editorship, Stevenson published twenty essays, four stories and one poem in the Cornhill. Thus he waged war against the prevailing culture in the pages of one of the most respected periodicals of that culture.

The other reason to spend time in London during 1878 was to see Fanny Osbourne, the American woman he had fallen in love with in France, who was for a period staying in London with her two children. She was married at the time, and ten years older than Stevenson, and he was living with her almost as openly as one could at that time.

In many ways, though, France came to feel more like home to Stevenson than London. He spoke fluent – though not always correct – French, and could pass in most places as a native French speaker – but not a native of the particular region he was in. Stevenson’s knowledge of French literature was prodigious, and in the mid-70s he spent most of his time with the painters in Barbizon, although he was there just as the movement founded by Corot, Millet, and Rousseau was beginning to die out. He was in Paris at the time of the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874, staying with his cousin Bob, who was studying painting in Paris at the time. There is some claim that he was the first to use the word Impressionist in English.

There are two points we can take from this. First, Stevenson, almost without trying, was enacting Matthew Arnold’s call from the previous decade for the British to become less provincial and to open themselves to the culture of the continent. And second, Stevenson was throwing himself into the life of the Bohemian, perhaps the most popular countercultural label of the nineteenth century. And Stevenson was not just a tourist in this bohemian culture; in Paris he was living a life of great poverty, refusing money from his parents on principle, furiously writing to support not only himself but Fanny and her children. I can’t prove this, but I think there is evidence that he raised extra cash by posing for a class of women painters – the class itself being a radical gesture. This modelling would be a desperate attempt to find some extra money comparable to the penniless drop-outs I recall in America who knew they could always donate blood to the Red Cross for a small remuneration of about $5.

Let’s look at one other picture of Stevenson in France, which offers us a vivid portrait of this young countercultural radical. At the end of the canoe trip through Belgium and France in 1876, which he recounted in his first book, An Inland Voyage, Stevenson was arrested in the small French town of Châtillon-sur-Loire. He kept this account out of An Inland Voyage and presented it to the public only after his father had died.

What happened was this, and it’s a story that has echoes throughout the 1960s, especially in America, where naïve radicals were busted and jailed simply because they did not know the right way to behave when confronted with the police. Here’s Stevenson’s description of his appearance (he speaks of himself in the third person as Arethusa, the name of his canoe):

The Arethusa was unwisely dressed. He is no precisian in attire; but by all accounts, he was never so ill-inspired as on that tramp; having set forth indeed, upon a moment’s notice, from the most unfashionable spot in Europe, Barbizon. On his head he wore a smoking-cap of Indian work, the gold lace pitifully frayed and tarnished. A flannel shirt of an agreeable dark hue, which the satirical called black; a light tweed coat made by a good English tailor; ready-made cheap linen trousers and leathern gaiters completed his array. In person, he is exceptionally lean; and his face is not, like those of happier mortals, a certificate. For years he could not pass a frontier or visit a bank without suspicion; the police everywhere but in his native city, looked askance upon him; and (though I am sure it will not be credited) he was actually denied admittance to the casino of Monte Carlo. If you will imagine him, dressed as above, stooping under his knapsack, walking nearly five miles an hour with the folds of the ready-made trousers fluttering about his spindle shanks, and still looking eagerly round him as if in terror of pursuit – the figure, when realised, is far from reassuring.

This was not long after the Franco-Prussian War, and Stevenson was stopped on suspicion of being a German spy. He joked with the police official, unable to take the situation seriously, but the joking just made his case worse. He was put in a damp, unlit cellar as his prison cell, and suddenly, as the chill air struck him, he became aware of the seriousness of his position. The culture he had been happy to run counter to had power over him after all. It may have been only half an hour that he remained in the cellar, but that was long enough. And to show that the established culture had the upper hand, he was released only because his travelling companion, Sir Walter Simpson, came to the rescue, and, being less radical than Stevenson, had the appearance of a true British gentleman, as well as the title baronet on his passport. (Stevenson, of course, had forgotten to bring his passport.) Respectability bailed him out. Even twelve years later, when he wrote this “Epilogue to An Inland Voyage“, he could not treat the event straight, but wrote in a self-mocking tone and joked about the bad verses in his notebook that the authorities would have been wise to destroy for the sake of posterity.

There was no quick rescue for the final countercultural event of the 1870s for Stevenson: his journey to California. There is a good story that says Fanny, now living near her husband in Monterey, sent Stevenson a telegram, presumably saying she was deathly ill. There is no evidence that this is how the story really occurred, but the romantic myth is probably more important: the free spirit, leaving his comfortable home to cross a continent to be with the woman he loved. In one sense, Stevenson ran away. He did not tell his parents that he was leaving, and cut himself off from any financial help from them. He broke ranks with his social class yet again by travelling only one step up from the lowest class of passenger. (He splurged on the slightly better accommodation because he needed his own room where he could write to pay for his expenses in America). (His ticket for the voyage from Liverpool to New York, by the way, was £6.)

In California, during the months of poverty while he waited for Fanny’s divorce to come through, Stevenson lived as he had on the boat – just one step up from the lowest – barely able to support himself. One consequence of this way of life is that Stevenson lived on a level not far from the outcasts of that society, and when he wrote later about California, and about America in general, he took a stance against the arrogant white American culture and spoke up for the Indians and Mexicans and Chinese.

Stevenson’s life as a man defying convention and sombre respectability took on, as I have hinted, the stature of a myth (he had a hand in this in his 30s), and like all myths, various people appropriated it for their own ends. But let’s move on from this and look at some of the ideas and principles that define Stevenson’s thought as countercultural.

II. His Countercultural Ideas

First of all, we have to recognise that he belongs to no school at all. The bohemians? Well, not quite, as I’ll show in a minute. The “noisy atheists”? No, not even them. The aesthetes? Yes, people sometimes attach this label to Stevenson, especially for his writings in the 70s, but it doesn’t quite fit. There was too much of the preacher in his writings. You couldn’t say he was a follower of any of the Victorian sages either, though he’d read them all, and we see influences from Carlyle, Ruskin, Pater, George Eliot and others. (Not Newman, however. I don’t recall any mention of Newman.) Perhaps the one contemporary school he has an affinity to is the American Transcendentalists. He championed Thoreau and Whitman in two major essays, and these two writers (though not, I think, Emerson) can be seen shaping much of his thinking on moral, social and even economic subjects.

Perhaps the core belief from which all the rest of Stevenson’s thought takes shape is a sense of the absurdity of all abstract thinking – calculations, moral principles, rules, dogma, conventions. Some of this derives from the scepticism of Montaigne, a very influential writer on the young Stevenson, but we must also figure in, the natural rebellion to the kirk, expected perhaps in a teenager who had been known for his precocious piety as a child. Whatever the specific influences, his fundamental position was that no doctrines could be trusted; they could all be reduced to nonsense. Here is a short fable Stevenson wrote in his twenties, which I’ll use to illustrate this position – and the potential bitterness that might arise from it.

THE SICK MAN AND THE FIREMAN

There was once a sick man in a burning house, to whom there entered a fireman.

“Do not save me,” said the sick man. “Save those who are strong.”

“Will you kindly tell me why?” inquired the fireman, for he was a civil fellow.

“Nothing could possibly be fairer,” said the sick man. “The strong should be preferred in all cases, because they are of more service in the world.”

The fireman pondered a while, for he was a man of some philosophy. “Granted,” said he at last, as a part of the roof fell in; “but for the sake of conversation, what would you lay down as the proper service of the strong?”

“Nothing can possibly be easier,” returned the sick man; “the proper service of the strong is to help the weak.”

Again the fireman reflected, for there was nothing hasty about this excellent creature. “I could forgive you being sick,” he said at last, as a portion of the wall fell out, “but I cannot bear your being such a fool.” And with that he heaved up his fireman’s axe, for he was eminently just, and clove the sick man to the bed.

This fable speaks of the absurdity of unexamined clichés; there are others just as incisive reducing institutional principles to absurdity – but they’re too long to read right now. These fables, incidentally, were not published in Stevenson’s lifetime. They were probably too scandalous for his wife to approve (she had a greater tolerance for respectability), and Stevenson’s respect for his wife meant he honoured her decision.

What do you do, then, if all principles are absurd? It is easy to move into pessimism or a witty scorn of all values, but for some reason Stevenson strongly resisted that direction. There are many ways of explaining this, but something pulled Stevenson inward to find his “pin-point of truth”, that inner voice, which is all we have to go on. (You can see perhaps how Stevenson comes to seem more and more modern: Is this Zen? Or Existentialism? Or even some odd kind of Post-Modernism?)

Stevenson tends to speak of this inner voice in Christian terms – though not a kind of Christianity his father or most other Christians of the time might recognise. Yet he will not insist on the Christian terms (which are only, after all, labels), and as you’ll hear, he is open to Darwinian language too. We must attend to that “higher spirit” or “soul”, behind all our thoughts and actions. “It may be the love of God,” he says; “or it may be an inherited (and certainly well-concealed) instinct to preserve self and propagate the race; I am not, for the moment, averse to either theory; but it will save time to call it righteousness” (Lay Morals, 26.25). So, righteousness it is, or conscience. But we are talking about something that can never be categorised or even set out clearly in words. It can never be directly communicated. “I do not speak of it to hardened theorists,” Stevenson says, as though “hardened theorists” were some kind of unclean beings; “the living man knows keenly what it is I mean” (25). That’s all he can say.

“That which is right upon this theory is intimately dictated to each man by himself, but can never be rigorously set forth in language, and never, above all, imposed upon another” (26). Does this relativistic sense of right lead to moral chaos? Yes and no. “When many people perceive the same or any cognate facts, they agree upon a word as symbol; and hence we have such words as tree, star, love, honour, or death; hence also we have this word right, which, like the others, we all understand, most of us understand differently, and none can express succinctly otherwise.”

It is our chief moral duty to keep alert to the promptings of this inner righteousness. Hence “the better part of moral and religious education” should be directed towards helping the person keep awake and “alive to his own soul and its fixed design of righteousness” (29). But of course it seldom is directed in this way. Most current education does not speak “the dialect of my soul […]. It is a calculating dialect, teaching respectability and profit in the future” training the young person to become rich so he can be received in society. “Received in society!” Stevenson exclaims; “as if that were the kingdom of heaven!” (30).

How does this faulty education work? Stevenson offers us a little drama, a kind of Banker’s Progress, in one of his very few essays to be rejected for publication – too radical, too pessimistic.

Why is [that man] a Banker? [Stevenson asks]

Well, why is it? There is one principal reason, I conceive: that the man was trapped. Education, as practised, is a form of harnessing with the friendliest intentions. The fellow was hardly in trousers before they whipped him into school; hardly done with school before they smuggled him into an office; it is ten to one they have had him married into the bargain; and all this before he has had time so much as to imagine that there may be any other practicable course. Drum, drum, drum; you must be in time for school; you must do your Cornelius Nepos; you must keep your hands clean; you must go to parties – a young man should make friends; and, finally – you must take this opening in a bank. He has been used to caper to this sort of piping from the first; and he joins the regiment of bank clerks for precisely the same reason as he used to go to the nursery at the stroke of eight. Then at last, rubbing his hands with a complacent smile, the parent lays his conjuring pipe aside. The trick is performed, ladies and gentlemen; the wild ass’s colt is broken in; and now sits diligently scribing. Thus it is, that, out of men, we make bankers.

How can a person have a chance to listen to that voice of the soul when he is taught instead to listen to the voice of social convention?

Christian teachings have their place here, yet as we would expect, not as rules to follow, but as a spirit to harmonise with. “Times and men and circumstances change about your changing character, with a speed of which no earthly hurricane affords an image” (112), so how can a precept, a formula based on the letter of the law, hope to define any direction for us? “Thou shalt not steal” – yes, of course, but what does stealing consist of? If I waste the money I have on things I do not need, am I not stealing from those who might have benefited more from the money I threw away?

How can we answer these questions? – by finding the character, or spirit, of Christ in the same way that a fiction writer gets inside the character in a story, or a historian “thinks himself into sympathy” with a historical figure – the kind of activity Stevenson demonstrated in his “familiar studies” of Burns, Villon and the others. And thus it becomes possible to be “of the same mind that was in Christ”, to “stand at some centre not too far from his and look at the world and conduct from some not dissimilar or, at least, not opposing attitude”. And standing so, he will find Christ’s words “as another sure foundation in this flux of time and chance”.

Locating each individual’s centre of truth in this divine connection deep within promotes a universal tolerance for others’ views while rooted firmly in our own views – not an easy balance in practice. For while we must follow the direction of our own soul, not others’, we must nevertheless remember that others “may be right; but so, before heaven, are we.” How dare we claim that we have any exclusive grasp of the truth? “God, if there be any God [notice how he reminds us to play it both ways], speaks daily in a new language by the tongues of men; the thoughts of habits of each fresh generation and each new-coined spirit throw another light upon the universe and contain another commentary on the printed Bibles; every scruple, every true dissent, every glimpse of something new, is a letter of God’s alphabet […]” (32). Is this a countercultural view? Well, it’s certainly not an orthodox view, either then or, probably, now.

So this is a (shortened) view of his ethics. How did he put these into practice? There is no time to go into detail, but here are a few social issues that follow from these views.

Stevenson always spoke out against his society’s treatment of women. He avoided the kind of good girls his social class expected him to mix with, girls who had been taught not to think for themselves but to be subservient first to their fathers and then to their husbands. Marriage was not an arrangement designed for the man’s convenience, but a constant struggle, with constant failure, of two equal people as they tried to understand each other, made all the more difficult because boys and girls were kept so far apart when growing up. “For marriage,” he proclaims at the end of the essay “Virginibus Puerisque”, “For marriage is like life in this – that it is a field of battle, and not a bed of roses” (25, 11) And so was his own marriage, to the divorced older woman who was experienced with guns, had lived as the single woman in a rough mining town, smoked cigarettes in public, and was never shy of speaking her mind.

And his views on prostitution were very firm. He never set stern moral prohibitions on prostitution; he looked at the person of the prostitute, not her “office”, as we might say. If we need sex before marriage, then paying a prostitute was a clean and honest arrangement. But when dealing with a prostitute, he insisted, we must act with great delicacy and respect. “[…] hardness to a poor harlot is a sin lower than the ugliest unchastity […]. The harm of prostitution lies not in itself but in the disastrous moral influence of ostracism” (Furnas, 55).

Another view arising from his beliefs was his challenge to us to appreciate a thing for its own sake, not for its usefulness to us, and certainly not for any usefulness far in the future. (In this regard he comes close to Matthew Arnold’s criticism of Hebraism, but my sense is that Stevenson worked out this position without much influence from Arnold, whom he certainly read but almost never mentions.) And after all, if we cannot rely on abstract principles, and if life is so complex and unreliable that it makes no sense to store up for tomorrow, then what is there left but to attend to the present moment. The respectable will tell us we are wasting our time in idleness, but “an intelligent person, looking out of his eyes and hearkening in his ears, with a smile on his face all the time, will get more true education than many another in a life of heroic vigils. […] it is all round about you, and for the trouble of looking, that you will acquire the warm and palpitating facts of life. While others are filling their memory with a lumber of words, one-half of which they will forget before the week be out, your truant may learn some really useful art: to play the fiddle, to know a good cigar, or to speak with ease and opportunity to all varieties of men.” (“Apology for Idlers”)

Here we begin to see that jaunty optimism for which Stevenson became famous, and then later, in the 1920s, ridiculed. But this optimism was not frivolous. It was a call for us to open up to the world around us, rather than accept what we are told. In particular it was a strike against another kind of countercultural gesture – the cynical, decadent melancholy dismissal of the world – the “Literature of Woe” or School of Obermann, as he called it. The inner voice, as Stevenson perceived it, was always calling on us to pick ourselves up after failure (and we are almost always sure of failure) and continue in the petty heroisms of everyday life. That spirit of Christ, with which our own souls resonate, leaves no doubt that if there are no exact principles to guide us, there are always lovers, friends, neighbours, or even strangers we must engage with and try to cheer and encourage on their way.

His views on money seem to be taken almost entirely from Thoreau, perhaps also Ruskin. We can claim as rightly ours only as much money as will satisfy our own needs and personal desires (desires we must strictly calculate in accordance with the voice of our conscience). All other money we may earn (or inherit) is given to us to pass on to others, in whatever way we see fit. “[…] it will be very hard to persuade me that any one has earned an income of a hundred thousand” (42).

And finally, let us end this part of the discussion with Stevenson’s distinction between the true and the false Bohemian, where we might see him define what makes a truly countercultural figure. The false Bohemian is the rebel who simply conforms to the literary type of a Bohemian. “The Bohemian of the novel, who drinks more than is good for him and prefers anything to work, and wears strange clothes, is for the most part a respectable Bohemian, respectable in disrespectability, living for the outside, and an adventurer. But the man I mean lives wholly to himself, does what he wishes and not what is thought proper, buys what he wants for himself and not what is thought proper, works at what he believes he can do well and not what will bring him in money or favour.” (46-47)

III. His Countercultural Writings

Finally, we must leave ourselves a little room for a few words about Stevenson’s writings themselves. By the end of the 70s, it would have been hard to define just what Stevenson’s literary direction was: there was such a variety of writing, in so many different forms. He had written several significant critical essays on French literature, and written two books of travel in France; many of his essays displayed his attempts to translate Impressionistic painting techniques into the medium of language, and he often in his essays used the technical language of painting; he had proved himself a knowledgeable historian of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in France and Scotland; he was a reviewer who had no hesitation in calling to task more prominent writers for their sloppy books; he was becoming a recognised essayist who seemed to combine the light familiarity of Hazlitt and Lamb with the moral serious (though not the earnestness) of Carlyle or Macaulay. And his output of fiction grew more frequent as the decade progressed. He was also collaborating on plays with W E Henley; in 1879 their dreams of taking the West End by storm and making lots of money might just have seemed realisable.

Yet none of these different kinds of writing seemed to conform to standard genres. There was always some idiosyncrasy that defied convention. Here are just a few examples.

In May, 1879, Leslie Stephen asked Stevenson to write an essay in response to a new book on Robert Burns by J C Shairp, the highly respectable Professor of Humanity at St Andrews and Professor of Poetry at Oxford, and an important member of the Church of Scotland. My sense is that Stephen turned to his resident Bohemian to provide an appropriately controversial reply to Shairp’s sanitised picture of Burns. Stevenson’s essay is still regarded by many Scots as a desecration on the holy memory of The Bard. Why? Stevenson insisted on confronting directly the many love affairs, or seductions, in Burns’ life. An account of Burns is false, he insisted, if it hides these details. But perhaps what was more scandalous was that Stevenson did not condemn Burns for his sexual adventures – but for the vanity that led him into these adventures, and the disregard for the women’s feelings or reputation. Yet in the end Stevenson’s essay is not harsh. He gently scans his brother man (this other Robert who also dressed in outrageous clothes and adopted poses), and forgives his weaknesses in the light of Burns’ honesty in facing the consequences of his actions. The hero is not the one who succeeds, but the one who admits his failures, makes amends, and tries again. So much both for the worshippers of Burns and for those waiting to pounce on anyone overstepping the moral rules. And so much for Principal Shairp, the epitome of Scottish respectability.

An early story like “A Lodging for the Night” is almost impossible to categorise, with its opening section combining historical fiction along the model of Sir Walter Scott and the horror of Edgar Allan Poe, yet drawing upon chiaroscuro lighting effects and what we might call counterpointed dialogue of three conversations going on at once – a remarkable blend, but not especially radical – but then daring to spend the second half of the story in a moral debate between François Villon and a rich old knight, about whether a thief has any less honour than a respectable nobleman (or the other way around? – whether a respectable nobleman has any less honour than a thief), just because one gains a few coins by filtering through the clothes of a woman lying dead in the street and the other gains a fortune by leading an army pillaging through the countryside.

And then there is Stevenson’s style, that aspect he became famous for – his attention to just the right word. That, of course, is a popular oversimplification. Our focus on his countercultural attitudes will show us that he was doing something much more important, and interesting, than merely taking care with his words. As my fellow editor Richard Dury says, there is “a kind of protest in the way he treats language: he is not going to play the game of using words in their codified dictionary meanings, he is not going to respect word-syntax (which verbs are transitive or intransitive, what preposition comes after a verb, what article must be used…). By playing with language and using it as he wants to, he is in part struggling against its constraining role.” The effect is to produce a kind of language that defies dictionaries or grammar books, appears perhaps as a French idiom or Scotticism, but is more likely Stevenson’s own use, in the end denying us the comfort of complacency. Here are a few examples taken at random:

“[…] To enjoy keenly the mixed texture of human experience, rather leads a man to disregard precautions, and risk his neck against a straw” (“Aes Triplex”, 77). “Risk his neck against a straw”? Is that some old proverb? Some phrase out of Horace? Does he expect us to know exactly what it means? Or does it startle us awake to receive an image like an impressionist painting – not quite clear, but understandable and much more alive than a conventional image.

The fear we experience “at the thunder of the cataract”, he tells us, might profitably be explained in mythic terms as Pan stamping “his hoof in the nigh thicket” (128). Who ever used “nigh” in this way, before a noun? If we look in the OED for help with these idiosyncratic idioms, we find many usages that are almost similar, but never quite identical. Stevenson presents us with a language of his own.

Does this make him superficial? A show-off? Yes, in part, and certainly this annoyed many readers – perhaps the very ones Stevenson wanted to annoy – those too self-important to play, those not open to new possibilities, even if only in the unusual placement of an adjective.

Or we can look at other features of the style, such as the juxtaposition of a formal eighteenth-century balanced sentence next to a casual colloquialism, or piece of slang, British or American. Can the reader make these leaps? There are also shifts of perspective and points of view, undermining the formal dynamics of reader and writer to produce the effect of sitting talking with an excitable friend, who uses his hands to point us in this direction or that to allow the conversation to explore all sides of a subject.

There is no time to go further into these stylistic features, all designed to keep us playing with the language, and the ideas, so we never settle into a set way of looking at things, which is the feature Stevenson most deplored in that respectable culture he had encountered and was countering in this early period of his early career.

Robert Louis, this is a great essay. I never knew about this aspect of Stevenson’s life. A cooler dude than I thought.

How have you been? Everything ok at home?