Podcast: Play in new window | Download

I was reading the other day a series of short meditations by Paul Ford, which appeared in the May issue of Harper’s Magazine. In an attempt to address the question “Is there an afterlife?” Ford contemplates the Grand Canyon. Here’s how he begins:

If you ever need to make your own Grand Canyon, start with a river and lift up the earth. As the ground rises the river will carry some of it away. Wait 7 million years, at which point tourists will come. Some will see eons of erosion at work; others will believe that, a mere 4,500 years back, God dragged His fingernail across the desert. (Paul Ford, Just like Heaven, in “Readings”, Harper’s Magazine, May 2010, p. 28)

That’s a good way to start – pulling us to an unexpected perspective on the “afterlife” by looking first at the Grand Canyon. The language we use to speak about the Grand Canyon might tell us something about how we see the afterlife.

We find two ways of looking at the Grand Canyon: “Some will see eons of erosion at work”. That’s one way of seeing it: an inhumanly prolonged natural process. Or we see this natural wonder as a work of God, who “a mere 4,500 years back … dragged His fingernail across the desert” – a couthie image of divinity casually playing in the dirt with his fingernail – not 4,500 years ago, but 4,500 years back – folksy, isn’t it? – yup, we built that barn only a coupla years back now. Given the way the American culture has moved lately, the only way to speak in a serious national magazine about divine creation is through such ironic nuance.

But Ford is aware that the usual non-religious language speaks of evolution, not erosion.

In Latin [he says], evolvere means “to unroll,” like a sacred scroll. The word “evolve” implies action. But evolution isn’t what happens; it ‘s what’s left over. Traits arise in populations, death sweeps though, some traits survive to the next generation. And repeat. Species don’t evolve – they erode. And the rock keeps lifting.

What we see here is a writer trying to adjust the language we use to speak about our world. Evolution, Ford suggests, is inaccurate, since rocks, and populations, do not act themselves on this grand scale, but are acted upon by natural forces. Erosion is a better word – better because it expresses more clearly the way so much of what we care about in our world lies passive to large, uncontrollable forces.

[Essay question: What large, uncontrollable forces are shaping your life at this moment?]

We, of course, can take our pick of which language we want to use, or better yet, we can exercise our imagination so that we become capable of holding at the same time all these different ways of talking, all these different perspectives, keeping our minds “supple, charitable, and bright”, as RLS puts it (“Morality of the Profession of Letters”). Here is the great virtue of parallax, measuring something by seeing it from many different perspectives – the gracious and gentle and sharp concept that can be considered the real hero of James Joyce’s masterpiece Ulysses.

Parallax. Taking the measure of our world through many different points of view. Do we see the world as having evolved, with the sense of its having unrolled – and also the sense of someone having rolled it up in the first place, this “sacred scroll”, as Ford calls it, whose unrolling reveals new things to us at each unfolding. Or erosion, coming from the word rodere, to gnaw, a rodent‘s action of chewing away at things. Good or bad, depending again on how we look at it. The gnawing away of what we valued? Yes, sometimes. But seeing the value of loss is the “One Art” Elizabeth Bishop praised in a famous poem:

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster,

Lose something every day.

Lose all that soil and rock eroded and in the end you get the Grand Canyon. And if we are tied in prison, we are happy to have the mice come and gnaw the rope binding us. A sculptor chisels at the marble (a kind of erosion) in order to reveal the beautiful shape hidden within.

Or we can see the world as a Creation. Evolution and erosion depend on scientific language (tinted with non-scientific imagery, such as the “sacred scroll” or the gnawing mouse). The imagery of Creation is mythic, and entirely human. The first thing the Bible speaks of is this act of creation, a creativity, then, lying at the very source of our universe. But being a myth, the Creation story does not tell us how the creation was accomplished (that’s the role of science); it gives us instead the pattern, a much deeper truth.

You and I, of course, are “supple, charitable and bright” enough to hold all these views at the same time. Not everyone can do this, however, as the following story shows us.

This story takes place several years ago, in a small class I was teaching, with students who knew each other well and so brought a relaxed – not to say holiday – atmosphere to the classroom.

One student calls out, “Hey, Professor, can I ask you a question?”

“Sure, what is it?”

“Are you an Evolutionist or a Creationist?”

“Sorry?”

“Yeah, like, are you an Evolutionist or a Creationist?”

“No, look,” I said, “you don’t really want to go into all that now, do you? It’s not a question of either/or. These are two different ways of looking at the world, both equally valid in separate ways.”

“Yeah, I know, but which one are you?”

Well, I could either drop the subject or impose my authority and point out the absurdity of his either/or choices. Or, I could be Socratic and throw the whole thing back to the class. Which is what I did. I do not know what inspired me to proceed as I did, but I surely must have been inspired. I couldn’t have come up with what follows on my own.

“Okay,” I said, “has anyone here ever created something?”

“Yeah,” said that first student, “Hey, I can pull down my fly and create something!”

“No, that’s pro-creation,” I said, throwing him off guard by taking him seriously on a different level.

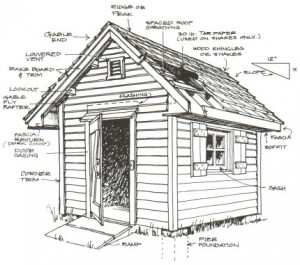

“Yeah,” said another student. “I guess I created something. A few years ago my Dad and I build a shed for our tools.”

“Oh, really?” I said. “And what did you do?”

“Well, we went out and bought the wood, and some more nails and screws, and the glass, and the stuff for the roof.”

“And did you do any planning first?”

“Sure. We looked at some magazines and talked to my Uncle Dave because he’d built a shed the year before. And we had to work out a kind of budget to see how much we could spend.”

“Good. So then what?”

“Well, we got the foundations right and put up the walls, and then we broke one of the panes of glass so we had to go out and get another one, and we painted it, and, well, there it was.”

“Uh-huh. And you created it?”

“Yeah. We both worked together and created it.”

“But, you know,” I said, “what you’ve described is the gradual evolution of the shed, from idea through plans through construction to final product. So was it both creation and evolution?

What happened next was amazing. His eyes lit up with a beautiful glow of comprehension. He actually held two different perspectives in his mind at the same time. Parallax. But five minutes later, the eyes dulled again; he lost the ability to hold both views together. Back to the old certainties of black and white.

I hope this was not an isolated moment of epiphany in this student’s education, but a part of a larger pattern of gradual enlightenment. And who knows how his subsequent education over the years may have evolved, what stronger imaginative and intellectual abilities would unroll for him, or what constricting prejudices and preconceptions would erode to reveal a truer, brighter self within, the self his Creator had made for him.

Evolutionist or Creationist…May I have a little slice of each please?

This is a beautiful article RLA. I thought about this very thing quite a bit this weekend as we spent time in the very spiritually rich and diverse town of Glastonbury.

I think there is room for both!

And look, even if you want the Creationist perspective, there are several different options: Genesis 1 and Genesis 2 see the Creation from different angles, and Psalm 104 offers another. As does John 1.1. And other places too.

Ah, but it’s so much safer and more comforting to have just one view of the world – and then destroy anyone who does not agree.

RLA

A brilliant little story that feels like a parable. As usual, your words reach deeper and e-ducate and have an impact on the reader (and listener, in this spoken version, very enjoyable!) showing your mission as a teacher.

Thank you for this little gem. I told the story to my son to illustrate the two perspectives. I look forward to more of your podcasts!

I see a flaw in your reasoning based on your little story. The flaw is in how you define words. The boy and his dad didn’t create anything, they simply ‘made’ something out of things that already existed. At best you could say that their plans for the structure were “creative” but still, compared to the word create that originates from Genesis 1, we simply make plans. The word for create in Genesis 1 is ex nihilio and means, out of nothing. Based on this definition, which is what Creationist would believe, we as humans make sheds.