https://eveningunderlamplight.substack.com/p/series-1011-walt-whitmans-song-of#details

“Twenty-eight young men bathe by the shore” while a twenty-eight-year-old rich woman gazes at their naked bodies splashing in the water, then goes out to caress them, in her vivid imagination.

Canto 1 The first episode in a series of talks bringing to life Dante’s Inferno, that great journey through Hell and all he sees there. We begin with Dante lost in a dark wood, and explore what it means to be lost, to lose control, to be stuck in the middle of things, and we get introduced to Virgil, who will guide Dante (and us) down through the nine circles of Hell.

Canto 2 Dante pulls back from the journey into Hell, thinking he’s not qualified to survive such an enterprise, but Virgil tells him of the three saintly ladies whose concern for him provides all the qualifications he needs. And we examine the way we can shift from cowardice to courage.

Canto 3.1 In Canto 3 we encounter the hard words written over the Gate of Hell, and then enter into the Infernal Regions. First Dante encounters those souls who never made any choices in life, just following what drew them along, and now we see them doing this in an exaggerated and gruesome way. And we come to the River Acheron, where the newly dead souls wait to be transported over the river where they will then fall down through the levels of Hell into their final place of torment. The discussion of this canto is continued in the second part of this episode.

Canto 3.2 We continue the discussion of Dante’s first encounters in Hell: the puny souls blindly rushing behind a nameless flag, representing most of the people who have ever lived, who have done nothing with their lives; and the fearful souls waiting to be ferried across the river. And why does Dante faint at the end of the canto?

You are invited to attend this week’s show, exploring tongue twisters, lies, truths, and other games of language. There’s a story here too, both literally and mythically true. And a great variety of music: Danny Kaye, Fraggle Rock, Gilbert & Sullivan, Leonard Cohen, Bruckner motet, Bob Dylan, CBS Jubilees, Simon & Garfunkel, Miles Davis from India.

You are invited to attend this week’s show, exploring tongue twisters, lies, truths, and other games of language. There’s a story here too, both literally and mythically true. And a great variety of music: Danny Kaye, Fraggle Rock, Gilbert & Sullivan, Leonard Cohen, Bruckner motet, Bob Dylan, CBS Jubilees, Simon & Garfunkel, Miles Davis from India.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Who are these characters in the Greek myths?This will be the first podcast in a series of podcasts speaking about Greek myths. First we have this introduction, and we’ll follow that with two episodes about Trickster gods. We know Hermes is the surpreme trickster god, and who is the other? I was surprised myself to discover that Athena, goddess of wisdom, takes her place as a trickster. We’ll see more of that in the next episode.

You can read the episode below, or listen to it through the links above.

Who are these characters in the Greek myths?

The Greek gods and goddesses are sometimes depicted as comic characters, figures we’d expect to see in a situation comedy. For instance, what do you make of this story, related by Homer in the Iliad, about the time when Hera wanted the Greeks to win the Trojan War, but Zeus, Hera’s husband (and brother), the king of the gods, was, at least for the moment, giving the Trojans the advantage in battle. So Hera made a plan to get her own way. She sidled up to Aphrodite, goddess of love (who incidentally was on the Trojan side, opposed to Hera’s Greeks), and Hera pleaded with Aphrodite: “You know that magic love belt you have, the one that goes around the thighs in that slinky way? The one that makes anyone who wears it sexually irresistible? Well, look, Zeus and I are, well, having a few little problems, you know, in bed, and I was just wondering, well, I mean you don’t need any extra equipment to make you irresistible you’re so sexy. But I was just wondering if I could just borrow that belt for just one afternoon? I’m sure that’s all I need to renew our marriage. Anyway, can I please borrow it? People who aren’t as beautiful as you, really need this kind of sex aid.”

Aphrodite fell for this and gave Hera the magic sexy belt. And it worked. Hera put it on and came over to Zeus, who was excited as he hadn’t been in a long time, at least towards her. She led him to their bedroom and let him do whatever he wanted. And then what happened? Well, you know, he just fell sound asleep. And now was Hera’s chance. While Zeus was asleep, the Greeks regained the advantage on the battlefield, and by the time Zeus woke up, it was too late to save the day for the Trojans. He’d been outwitted, just like the goofy father on an old television comedy.

This is one kind of story about the Greek gods and goddesses.

Another kind of story from Greek mythology shows these characters as participants in gruesome horror movies, as when Tantalus, a mortal man, was giving a dinner to the gods at his palace, and just to test whether they really were omniscient and knew everything, he killed his little son Pelops, cut him up, and served the pieces in a stew. The gods knew perfectly well what was going on and managed to restore Pelops’ body and bring him back to life. But, alas, Demeter, the goddess of plenty, had not been in a party mood, lamenting for the loss of her daughter, and she absent-mindedly ate one of the pieces – Pelops’ shoulder, in fact. When the boy’s body was restored, therefore, his shoulder was missing, and they had to construct a new bionic shoulder for him out of ivory.

That’s bad enough, but then the story moves into a different mode: not a horror movie, but some kind of sexploitation. The restored Pelops was so beautiful that the god Poseidon fell in love with him and abducted him, keeping him for his pleasure on Mount Olympus until the boy grew to adulthood, when, presumably, his attraction for the god diminished and he was allowed to return to earth.

What is going on in these stories? They seem to feed the worst impulses in us. Oh, yes, there are some uplifting stories, and some happy endings, but, you know, there are not that many of them compared to the horrible endings.

And yet these stories have lived on through the centuries, inspiring poets, storytellers, dramatists, artists, sculptors – and now cartoonists and video-game designers. I think they live on because they’re good stories, but also because – whether we are consciously aware of it or not – they illustrate for us some quite serious truths about ourselves and the world we live in. They can add extra depth to our own lives if we give them some serious consideration, letting our imagination open to them as we would open to serious poetry. These gods and goddesses, monsters and heroes, are, we discover, personifications of (or metaphors for) spirits or forces present at all times in our lives and shaping our world.

Eros (or Cupid), for instance, the god of love, is on one level just this annoying little kid who goes around shooting gold-tipped arrows at people, who then fall in love with whomever they encounter next. A silly Valentine’s Day card image, but this boy with the magic arrows is also an externalisation of that moment of falling in love at first sight, a delightful, painful event many of us have experienced. And that unrealistic externalisation can explain what it’s like to fall in love at first sight in a way that no other explanation can do for us. Our modern scientific explanations of biology, chemistry, or psychology can speak of falling in love in terms of hormones, or psychological need, or an ancestral procreative urge. We are justly proud of our scientific explanations, but, as my man Robert Louis Stevenson has written,

there will always be hours when we refuse to be put off by the feint of explanation, nicknamed science; and demand instead some palpitating image of our estate, that shall represent the troubled and uncertain element in which we dwell, and satisfy reason by the means of art. Science writes of the world as if with the cold finger of a starfish; it is all true; but what is it when compared to the reality of which it discourses?

We can draw upon our inherited mythic images, Stevenson reminds us, that will express the feeling of these events, “the troubled and uncertain element” of falling in love. Thus we can connect to this irresponsible little deity, much of the time depicted blindfolded to remind us that we often seem to fall in love with someone we have not been seeking, someone we have not first approved of with our eyes. The love comes to us feeling as if it’s a random connection, as if someone blindfolded had arranged this. And it can come with such violence and shock that it feels like we’ve been pierced by some outside force, with no power to resist. Some arrow coming out of the blue, for instance. The Eros myth has captured the feeling of falling in love at first sight in a way that scientific explanation of chemicals and impulses cannot.

The myth is not “true” in the literal sense. There is no god Eros, or Cupid; there are no magic arrows. But on the other hand, the myth is truer than science’s cause-and-effect truths since it describes the human response to the event, rather than just the mechanical operations going on.

The Greeks knew what they were talking about when they told stories of these mythic deities. They were finding ways of speaking about what it feels like to be human. And their myths can provide us now with detailed images that articulate many of the human feelings and behaviours we experience all the time. They give us a language to understand ourselves and our world more deeply. Our task is to be grateful, and to play with our inherited imagery.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Let me tell you a little story about Meg, a top advertising executive in Los Angeles, who discovered her connection to Cinderella and thereby found herself.

Meg was successful. She was making something like $400,000 a year, but was itchy, never content with herself. She spent almost a quarter of her income on clothes, make-up and “body work”. She was a little over fifty years old, still pretty glamorous, especially in her expensive clothes, but her confidence was weakening. She found it hard to show up at business meetings, or if she did show up, she felt compelled to leave as soon as she could get away. She had this fear that sooner or later the other people would discover that she was actually not as attractive as they had thought she was. She had this sense that deep down she was worthless and someday she would be exposed. Read the rest of this entry »

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

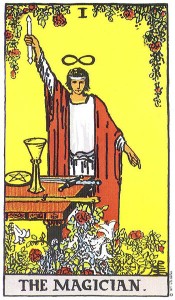

[Here is the second Tarot meditation, on The Magician. With card Zero we met the Fool, walking off the cliff to start his journey (our journey) deep within, and now we meet this Magician, who points and offers what we need.]

The first person we come across after our fall from the Fool’s ledge is the Magician, standing there calm and still to greet us. This is a sumptuous picture, full of warm yellows and reds, framed by flowers.

As the Fool’s card moved from the upper right to lower left, so this card moves from upper left to lower right. This opposite movement arrests our fall. We are on the earth again.

The right hand looks like it is raised in greeting, but we discover that it is holding something, pointed to the heavens. The left hand certainly is pointing to something for us. Taken together both hands seem to be offering one complete gesture, which unifies heaven and earth, above and below. Read the rest of this entry »

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

[This week I would like to read to you a fable by Robert Louis Stevenson: “The Song of the Morrow”. Stevenson’s collection of fables and fairy tales – which was too scandalous to be published in his lifetime – is called in the manuscript Aesop in the Fog. That’s a hint to us not to expect easy morals. Things are more complicated, to suit our foggy world in which so little can be fully understood or communicated. Let the story stir you and move you, come back to it over a number of days and let the resonance play in your imagination and deep in the core of your self, while your intellect takes a holiday and does not try to figure this out. Just let the words and the images work on you. Then you may find some hints and glimpses of meaning, and maybe later you’ll understand more. There’s no rush. Let us know what you think. RLA]

The King of Duntrine had a daughter when he was old, and she was the fairest King’s daughter between two seas; her hair was like spun gold, and her eyes like pools in a river; and the King gave her a castle upon the sea beach, with a terrace, and a court of the hewn stone, and four towers at the four corners. Here she dwelt and grew up, and had no care for the morrow, and no power upon the hour, after the manner of simple men. Read the rest of this entry »

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

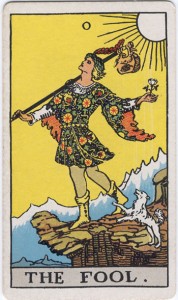

Our journey begins with the Fool, a trickster, the one who disrupts our complacency and calls us out of ourselves to a world of joy and liberation. Court jesters always had special dispensation to say whatever they wanted, even if it was irreverent and disrespectful. In fact the Fool was expected to be irreverent and disrespectful. That was his role.

The Fool is also a pain to have around, never letting us rest, always trying to stir us up. Yet the Fool always knows when to stop; he is benign and if he harms us, it is only for our own good. He annoys but never destroys us. Read the rest of this entry »

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

I was reading the other day a series of short meditations by Paul Ford, which appeared in the May issue of Harper’s Magazine. In an attempt to address the question “Is there an afterlife?” Ford contemplates the Grand Canyon. Here’s how he begins:

If you ever need to make your own Grand Canyon, start with a river and lift up the earth. As the ground rises the river will carry some of it away. Wait 7 million years, at which point tourists will come. Some will see eons of erosion at work; others will believe that, a mere 4,500 years back, God dragged His fingernail across the desert. (Paul Ford, Just like Heaven, in “Readings”, Harper’s Magazine, May 2010, p. 28)

That’s a good way to start – pulling us to an unexpected perspective on the “afterlife” by looking first at the Grand Canyon. The language we use to speak about the Grand Canyon might tell us something about how we see the afterlife. Read the rest of this entry »